My Father’s City

My father was a city boy in exile,

though he wouldn’t have mentioned it—

self-pity was not in his nature.

Our address was on a rural route,

a gravel road—one of a handful of houses

in the midst of pastures and farm fields.

Every time a car went by, it left a plume of dust

that sifted into our lives, bleached the willows

and lilacs to ghosts in our yard.

To my brother and me the road

was a dragon-like creature, breathing

white clouds, promising escape.

My father was in no hurry to go anywhere.

He’d been shipped to Burma and back

in the service of country and war—

the last thing he wanted was another itinerary.

He was content, I think, to let the dust settle

around him, like a slow-motion burial.

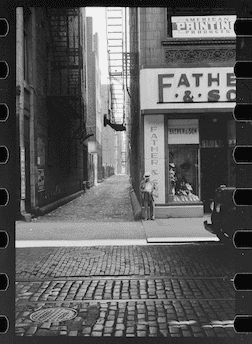

But he’d tell city stories—origin tales

of sorts—how he’d skip school,

catch the Clark Street trolley,

sneak into Wrigley Field. All his

side-street stickball heroics, those

alleys bloodied by Al Capone.

Try as I might, I couldn’t live his mythology.

I couldn’t ride my bike on imaginary streets

or hop a streetcar that wasn’t there.

I might skip school, sure—just to nap

in orchard grass, watch the red lights blink

on the radio towers all the lonely afternoon.

He waited, I think, for the city

to come to him—a sidewalk, sewer maybe,

a street sign, anything.

He waited. Raked the gravel

in the ditch back onto the verge.

Weeded his driveway.

Each year the countryside shrugged,

turned its back on curbing

and house numbers.

Each year the road issued

another bible-full

of dust.

It settled like the good news

in the corn and low places—

another dry run for the deluge.

When the city caught up with him,

he’d left it to me for good. I carry it inside,

folded like a map or a wing.

It’s blue, like its lake,

strangely warm and gentle,

despite the wind and cold. It’s patient.

Stands on the edge of the prairie,

waits for the dust to settle,

and its son to find his way home.

Published in San Pedro River Review Spring 2021